The 58th Special Breakfast Meeting featured President of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), Professor Hitoshi Nakagama.

Professor Nakagama, who assumed his position as President of AMED in April 2025, discussed AMED’s past achievements and the direction for its initiatives during its 3rd Phase.

<Key points of the lecture>

- In the ten years since AMED was founded, it has built a system that provides unified support for medical research from basic research to practical application. Annually, AMED invests approx. 160 billion yen to advance a wide range of studies from basic research to practical application, with its focus mainly on supporting research that is near the practical application phase. By establishing the Strategic Center of Biomedical Advanced Vaccine Research and Development for Preparedness and Response (SCARDA) and strengthening global collaboration, AMED is also advancing efforts to create a system for infectious disease preparedness with a view toward global expansion. Support provided through this system is focused on the practical application of research findings.

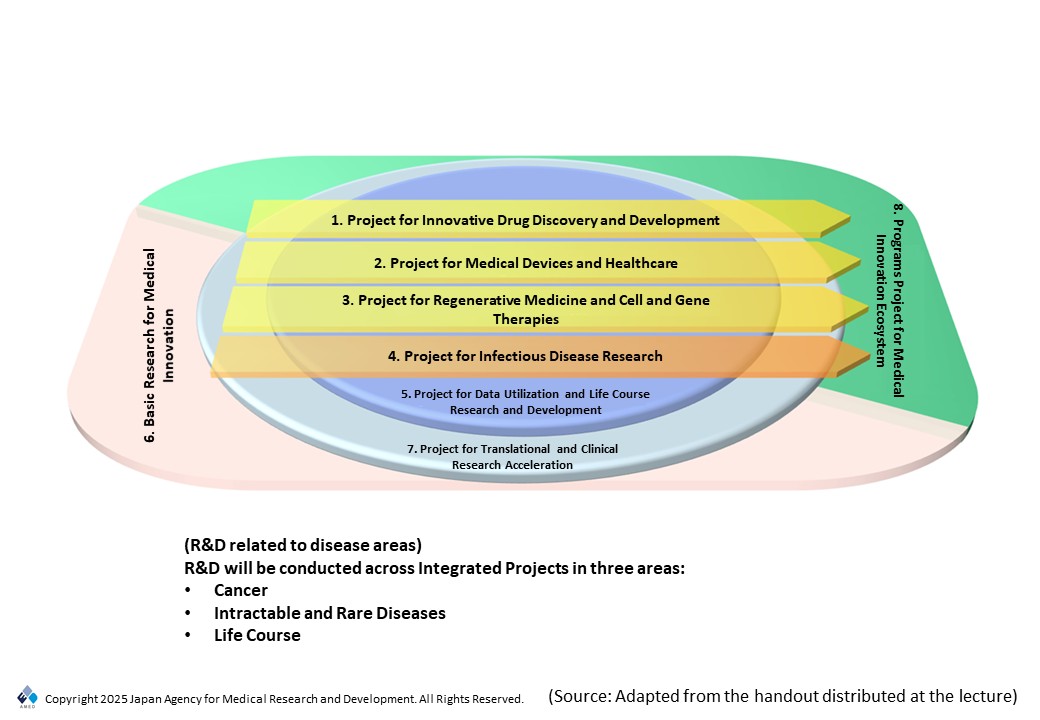

• During the 3rd Phase of AMED, which began in April 2025, AMED will remain centered upon and expand the six Integrated Projects from the 2nd Phase, and will promote the practical application of findings through the effective use of data and clinical research acceleration with a focus on areas including drug discovery, medical devices, regenerative medicine, and infectious disease. With regards to operations, AMED will expand collaboration among projects, opportunities for co-creation with industry and academia, and basic research to reinforce systems that lead to the efficient application of noteworthy basic research assets centered on international expansion and healthcare digital transformation (DX).

• Moving forward, AMED aims to serve as a link between the domestic drug discovery ecosystem and the international drug discovery ecosystem by collaborating with venture capital (VC) firms from Japan and overseas and by promoting international brain circulation. Moving forward, AMED will establish frameworks that bridge public and private funding to strengthen Japan’s drug discovery ecosystem in Japan and overseas.

■Overview of AMED and achievements from its 1st and 2nd Phases

By providing the health sector with unified support for R&D from basic research to practical application, AMED’s activities aim to assist progress in R&D and to establish an environment that can be used effectively in health sector R&D. It has been ten years since AMED was established, and it is currently in its 3rd Phase, which began in April 2025.

Results in R&D promotion

Annually, AMED invests approx. 160 billion yen to support approx. 2,600 research proposals, about 25% to 30% of which are adopted as new projects. As for the distribution of research funds, the largest number of proposals are provided with 10 million yen to 25 million yen annually, followed by those provided with 25 million yen to 50 million yen annually. This occurs because vast funding becomes required as research aiming for practical application advances into the later stages of development. One characteristic of AMED is that its research grants are more generous than other public organizations. In fact, obtaining research funding from AMED requires applicants to spend an average of about two years and eleven months to prepare and accumulate findings through research conducted through other sources of funding. This has created circumstances in which research projects apply for and are adopted as AMED projects after accumulating findings and reaching the stage where their focus is turned to practical application.

At the same time, AMED also recognizes the importance of frameworks that produce results while fostering research, and the ratio of proposals that are adopted is higher for those in the development phase compared to the basic research and practical application phases. Around 60% of AMED’s research funds are provided to universities and other research institutions, followed by independent administrative agencies, national testing and research institutions, and private sector companies. By area of disease, AMED’s main focus is cancer followed by infectious disease control, including for emerging and reemerging infectious diseases. Other areas where AMED devotes a significant amount of research funding include cardiovascular disease and neurological disease.

Examining major achievements of AMED projects in detail, over 6,000 papers in basic research have been published, 357 proofs of concept (PoC) in applied research have been acquired, and 434 clinical trials have been conducted. Among those trials, 40 received regulatory approval and have achieved practical application. Expectations are high for AMED to clearly indicate where the “exits” are for research and to support research in a cross-cutting manner that spans all modalities or drug discovery methods.

The establishment of the Strategic Center for Advanced Research and Development (SCARDA)

In recognition of the importance of infectious disease crisis preparedness, the Strategic Center of Biomedical Advanced Vaccine Research and Development for Preparedness and Response (SCARDA) was established within AMED in accordance with the Strategy for Strengthening the Vaccine Development and Production System approved by Cabinet Decision on June 1, 2021.

The three key functions of SCARDA are: (1) gathering and analyzing a broad scope of information; (2) performing strategic decision-making; and (3) providing flexible funding. To promote vaccine development as part of the vaccine strategy, 51.5 billion yen has been allocated to the “Japan Initiative for World-leading Vaccine Research and Development Centers,” 150 billion yen to the “Program on R&D of new generation vaccines including new modality application,” and 50 billion yen to the “Strengthening Program for Pharmaceutical Startup Ecosystem.” In this manner, SCARDA is working to ensure Japan has a system in place for the rapid development of therapeutics in the event of an emergency.

Initiatives from Japan in global collaborative research

Currently, there are concerns about the decline of Japan’s global standing in science and technology. In addition to providing financial support, expectations are high for AMED to help address those concerns by also providing support that expands international brain circulation, international collaboration, and international joint research for the practical application of research findings.

For example, Japan has been collaborating with the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) for over 60 years, starting with the establishment of the U.S.-Japan Cooperative Medical Sciences Program (USJCMSP) in 1965. As for collaboration with Europe, AMED has signed a cooperative agreement on infectious diseases with the Health Emergency Preparedness and Response Authority of the European Commission (HERA). AMED has also built cooperative frameworks with various countries for joint research based on Memorandums of Cooperation (MOC) or the e-ASIA Joint Research Program.

■The direction of AMED efforts in its 3rd Phase

AMED’s approach to further promoting R&D through Integrated Projects

While reflecting on past achievements and challenges, the Integrated Project framework centered on items like modalities adopted during the 2nd Phase will generally remain in place during the 3rd Phase. This will allow for consistency in research to be maintained while enabling efforts for further progress and practical application. Specifically, AMED has advanced R&D in various areas of disease under six Integrated Projects: “Innovative Drug Discovery and Development,” “Medical Devices and Healthcare,” “Regenerative Medicine and Cell and Gene Therapies,” “Genome and Health-Related Data,” “Basic Medical Research,” and “Basic Research for Medical Innovation.” In addition to contributing to further clarifying development objectives and to fostering exit-oriented attitudes toward research among researchers, the Integrated Project framework has also reinforced collaboration among projects.

During its 3rd Phase, AMED will retain parts of this integrated project framework, with “Innovative Drug Discovery and Development,” “Medical Devices and Healthcare,” “Regenerative Medicine and Cell and Gene Therapies,” and “Infectious Disease Research” serving as major projects (see Fig. 1). We will also expand the Project for Data Utilization and Life Course Research and Development, which supports these major projects. This will aim to bridge gaps to practical application and accelerate clinical development through collaboration with basic research asset development and basic research. Finally, there are high expectations for AMED to spur innovation and reinforce the drug discovery ecosystem to serve as “exits” for R&D. Disease areas will be broadly arranged into three categories: cancer, intractable and rare diseases, and the life course (which encompasses lifestyle diseases and other diseases related to risks that accumulate at each life stage).

AMED’s total budget for FY2025 is expected to be approx. 200 billion yen. This includes an initial budget of 123.2 billion yen and an adjustment budget of 17.5 billion yen to be allocated from endowment projects and the President’s discretionary funds. As for how the budget will be allocated, the largest portion will be allocated to the “Innovative Drug Discovery and Development” project.

The future direction of AMED operations

AMED has set the following directions to guide its operations during its 3rd Phase.

- Strengthen collaboration among projects

Instead of fostering each project individually, AMED aims to enable a smooth transition to practical application by addressing issues present between each phase of R&D by strengthening collaboration among projects. To do this, AMED is currently advancing efforts to build and introduce internal mechanisms for pairing and matching. - Collaborate with industry and academia and engage in private licensing from the initial stages of R&D

AMED will work to increase the probability that projects successfully reach practical application by involving companies from the initial stages of R&D. - Enhance basic research to generate results that lead to widespread adoption in and contribute to society

Given the importance of advancing basic research while keeping widespread adoption in society in mind, AMED aims to provide continuous and stable support to enhance basic research that contributes to generating results. - Promote international expansion

Making full use of its global research network to deepen collaboration in basic research asset development and among projects, AMED will establish a foundation for producing excellent research results. It will also be important for AMED to continuously and actively contribute to building an environment in which the domestic pharmaceutical market attracts international attention by advancing domestic R&D that proactively incorporates global needs. - Advance the digital transformation of R&D in the health sector

Utilizing technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and quantum technology, AMED aims to contribute to creating a society of healthy longevity by producing and verifying new evidence based on big data and the effective use of personal health records.

Based on these principles, AMED aims to build a system for promoting the practical application of promising basic research assets with greater efficiency by gathering information, including knowledge from other countries; by addressing issues related to collaboration across projects; and by providing support that serves as a bridge for companies.

■AMED’s recent initiatives

Utilizing discretionary funds to reinforce existing research projects and accelerate the establishment of new projects

The AMED President’s discretionary funds are an adjustment budget used to reinforce existing research projects and to accelerate the establishment of new projects. Effective methods of using these funds are determined through internal discussions at AMED as well as through consultations with relevant ministries and agencies. The three items described below provide specific examples of how these funds are being utilized in FY2025.

- Developing a system program to support surgical planning for pediatric patients with congenital heart disease

Significant variation in cardiovascular structure means pediatric patients require personalized surgical planning. With sights set on the international expansion of the program that this initiative is developing, discretionary funds are being used to support the development of clinical trial protocols that comply with other countries’ pharmaceutical regulations. We hope that this will encourage other countries to adopt Japan’s innovative medical support systems. - R&D related to elucidating the pathophysiology of schizophrenia

Aiming to elucidate the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, studies on synaptic behavior during memory formation and on molecules related to that process are now advancing. The discretionary funds are being utilized to promote collaboration with another research group that has developed a new method of molecular design in hopes that it will advance efforts to identify or develop new therapeutic targets and therapeutics for schizophrenia. - Establishing and expanding a foundation for rapid genetic diagnosis in critically ill newborns

Japan’s diagnostic infrastructure only had one center for rapid genetic diagnosis in critically ill newborns, which was located in eastern Japan. There were also issues related to systems for data integrity and response. Discretionary funds were used to establish a new center in western Japan and plans are in place to reinforce data security and to strengthen the system for genetic counseling. Expectations are high for these efforts to accelerate and streamline genome diagnosis and elevate diagnosis rates.

Strengthening the drug discovery ecosystem

Achieving the practical application of research findings or bringing research results to market require vast amounts of funding. However, as it is difficult for AMED to fully cover these costs with public funds, cooperation from venture capital (VC), investors, and pharmaceutical companies is required. To support efforts to raise private funding in the early stages of research, the domestic drug discovery ecosystem must be strengthened. Given these circumstances, AMED is currently advancing the new initiatives described below.

Promoting human resource development and international brain circulation

AMED recognizes a gap in coordination that links researchers with VC, investors, and pharmaceutical companies, as well as an insufficient human resource pool for filling coordinator roles. By proactively recruiting international human resources, AMED is advancing efforts to expand the domestic drug discovery ecosystem.

(Photo: Kazunori Izawa)

Collaborating with registered VCs

Based on their track records of investment in drug discovery, AMED has selected 30 VCs as “registered VCs.” By combining support from registered VCs with the subsidies AMED provides to drug discovery startups, AMED is working to accelerate drug development. As around half of the registered VCs are international firms, this initiative is helping to create opportunities to inform the international community about basic research assets from Japan and to acquire support from overseas investors.

Linking national and international ecosystems

While serving as a foundation for fostering basic research assets in Japan, it is also important for AMED to promote global drug discovery through collaboration with drug discovery ecosystems overseas. AMED is expanding activities in which it steadily provides thorough introductions of Japan’s basic research assets to related institutions, investors, and other such parties. These efforts are expected to contribute to the development of Japan’s drug discovery ecosystem as well as to encouraging further participation from domestic Japanese pharmaceutical companies.

The lecture was followed by a Q&A session with the audience. Participants held a lively discussion on topics including the need to strengthen the evaluation system to support practical application, specific details on reinforcing systems to promote the international expansion of initiatives, methods of developing human resources, and fields of medical research in which the utilization of DX should be advanced.

(Photography: Kazunori Izawa)

■Profile

Hitoshi Nakagama (President, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED))

Professor Hitoshi Nakagama graduated from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Medicine in 1982. In 1990, he was appointed Assistant Professor at the Third Department of Internal Medicine at that same university. The following year, in 1991, he began serving as a Research Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Cancer Research (CCR) in the US. He was awarded a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1992. At the National Cancer Center Research Institute (NCCRI), he was appointed Director of the Division of Carcinogenesis in 1995, and later went on to serve as Director, Department of Biochemistry; Deputy Director; and Director. He was appointed Chief Director and President of the National Cancer Center in April 2016 and President of the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) in April 2025. His research is centered on the analysis of environmental and genetic factors of human carcinogenesis and the molecular mechanisms of those factors. His areas of specialty are molecular oncology, cancer genomics, and environmental carcinogenesis.

Thank you for your continued support of Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI).

Mr. Shinsuke Muto(Board Member, HGPI) was appointed as Vice Chairman at a meeting of the Board of Directors held on June 23, 2025.

Mr. Hiroaki Yoshida(former Vice Chairman, HGPI) will continue to be involved in HGPI activities as Board Member.

Thus with this renewed structure, HGPI looks forward to working even harder to develop and strengthen Japanese civil society. We would like to express our sincere appreciation for your continued support.

■Board of Directors(as of June 23, 2025)

Kiyoshi Kurokawa (Honorary Chairman for life)

Ryoji Noritake (Chair and CEO)

Shinsuke Muto (Vice Chairman)

Hiroaki Yoshida (Board Member)

Kohei Onozaki (Board Member)

Yusuke Tsugawa (Board Member)

Ryozo Nagai (Board Member)

Satoko Hotta (Board Member)

Kenji Maekawa (Auditor)

Kaoru Matsuzawa (Auditor)

* With the exception of Ryoji Noritake, Board Members serve part-time and pro bono.

We were honored to welcome Dr. Keiko Morimitsu, Director-General of the Health Policy Bureau at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, as our guest speaker at the 57th Special Breakfast Meeting hosted by Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI).

In July 2024, Dr. Morimitsu became the first woman to be appointed Director-General of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) Health Policy Bureau. In this lecture, she discussed efforts to create a healthcare provision system that ensures peace of mind for citizens through categorization and collaboration in regional health services.

<Key points of the lecture>

- As a result of efforts to foster collaboration among regional health institutions and categorize them by function under existing Regional Medical Care Visions, the number of care beds reached 1,193,000 by 2023, almost achieving the targeted number of care beds for FY2025. While there has been noteworthy and steady progress in transitioning patients with low healthcare needs to in-home care, care bed allocation remains a challenge.

- With sights set on 2040, the year that healthcare and long-term care demand is projected to peak, the MHLW has been advancing efforts to consider “New Regional Medical Care Visions.” Two key issues that require consideration are the increase in ambulance transports due to population aging and regional disparities in and greater demand for in-home care. The MHLW is examining various steps to address these issues, including establishing health systems that reflect the unique healthcare needs of senior citizens, the state of emergency transports, and the characteristics of each community. The MHLW is also reviewing how care beds are currently categorized by function.

- The uneven regional distribution of physicians is a prominent issue. This gap between regions is currently expanding, and some are concerned about physician shortages, particularly in areas with small populations. To address this, the Government has formulated the Comprehensive Package for Correcting the Uneven Distribution of Physicians and is advancing efforts with a multifaceted approach. That approach includes providing economic incentives and strengthening collaboration among healthcare institutions in communities.

■What are Regional Medical Care Visions?

The Regional Medical Care Visions initiative aims to establish systems providing efficient, high-quality, and appropriate healthcare by categorizing health institutions by function and by fostering collaboration among them while taking into account factors such as mid- to long-term demographic shifts or changes in healthcare demand in terms of quality or volume for each region. Regional Medical Care Visions were institutionalized under the 2014 Act for Securing Comprehensive Medical and Long-Term Care. They were included in the Medical Care Plan the following year.

Current Regional Medical Care Visions aim to respond to population aging and healthcare disparities among regions with a target date of 2025, when the baby boom generation will be age 75 or older. Their specific goals include categorizing care beds into four categories (the advanced acute phase, the acute phase, the convalescent phase, and the chronic phase) to estimate the number of care beds that will be necessary in 2025, and to establish high-quality healthcare provision systems that are tailored to each community by categorizing health institutions by function and building collaborative ties among them through discussions among local health professionals.

Efforts under existing Regional Medical Care Visions have advanced in accordance with the August 6, 2023 report of the National Council on Social Security Reform, which was a government expert panel for examining the future structure of Japan’s social security system established in November 2012 under the Social Security System Reform Promotion Act enacted earlier that year in August. Activities at that Council continued until August 2013. Topics covered in its discussions included responding to birthrate decline, population aging, and the widening budget deficit, as well as systemic reforms for achieving sustainability in areas like pensions, healthcare, long-term care, and birthrate measures. Its final report laid the foundation for the integrated reform of the social security and tax systems. With sights set on 2025, the year that the baby boom generation reaches age 75, the report included estimates for healthcare demand and care beds, and recommended taking action to secure health facilities and personnel to suit the categorization of care beds in a manner tailored to each region. Furthermore, recognizing that the necessary health systems would differ by community, the report also identified the need for “homegrown healthcare,” which is a concept in which each region identifies the ideal structure of healthcare and long-term care for itself.

The Government has established financial and institutional measures to support local governments’ efforts to promote medical care visions that meet their respective circumstances. For example, starting in FY2014, the Government has been providing financial support using revenue from a consumption tax increase through a framework established in each prefecture called the “Comprehensive Fund for Regional Medical and Long-term Care.” Each prefecture can form its own prefectural plan that reflects local conditions and that it can then use as the basis for healthcare- and long-term care-related projects.

■Evaluating current Regional Medical Care Visions

Estimates show that if current Regional Medical Care Visions fail to make progress in collaboration and the categorization of care beds by function, population aging will result in the need for approx. 1.52 million care beds by 2025. However, current Regional Medical Care Visions are on track to lower the number of care beds that will be necessary to approx. 1.19 million. This was accomplished through three initiatives: redistributing healthcare demand from patients in general care beds who meet C3 treatment standards or below (which denotes people who require relatively few healthcare resources) to in-home care and other forms of care; redistributing healthcare demand from 70% of Treatment Category 1 patients (who are determined to have the least need for care) in convalescent care beds to in-home care and other forms of care; and by advancing efforts to eliminate regional disparities in hospital acceptance rates for convalescent care beds.

According to the 2023 Hospital Bed Classification Report, there were 1,193,000 care beds as of 2023, which shows Regional Medical Care Visions have almost achieved their target of 1.19 million care beds. As for the breakdown, general care beds for patients graded C3 or below decreased from 118,000 to 43,000 beds (a 64% decrease); convalescent care beds for Treatment Category 1 patients decreased from 125,000 to 30,000 (a 76% decrease); and chronic care beds for patients other than for Treatment Category 1 decreased by 113,000, almost meeting the target of 119,000 beds. As we can see, there is steady progress in transitioning patients with low care needs to in-home care, but as of 2023, there were lingering challenges in the distribution of care beds for the advanced acute care, acute care, convalescent, and chronic phases. In particular, a large proportion was still being allotted to acute phase care beds, where current circumstances differ from initial estimates.

■New Regional Medical Care Visions for 2040

Background

Because the target year for the Regional Medical Care Visions initiative is 2025, in March 2024, the MHLW hosted a study group on “New Regional Medical Care Visions” with sights set on 2040. A summary of their discussions was compiled later that year in December.

It is projected that over 10 million people will be age 85 and older by 2040, which is when combined demand for healthcare and long-term care services will peak. Given this projection, in addition to hospital functions, it will be necessary for “New Regional Medical Care Visions” to take regional healthcare provision system as a whole into account, and include factors like primary care physician services, in-home care, and collaboration among healthcare and long-term care.

Main points for consideration

Against this backdrop, two main points should be emphasized when considering “New Regional Medical Care Visions” for 2040. First is that ambulance transports for senior citizens will increase both in number and as a share of all transports. From 2020 to 2040, the number of emergency transports is projected to increase by 36% for people age 75 and older and by 75% for people age 85 and older. Today, it is difficult for ambulances to secure hospitals to accept their patients, and this is likely to become even more difficult in the future. Focusing on the severity of those being transported by emergency services, there are significant differences in trends among those ages 15 to 64 and those age 65 and older, with one notable characteristic being that the number of senior citizens with relatively mild to moderate conditions being transported is increasing. On top of this, leading factors for acute hospitalization and necessary healthcare services are very different for senior citizens compared to other age groups. When considering how to structure the healthcare provision system of the future, senior citizens’ unique needs and circumstances surrounding emergency transport must be kept in mind.

The second main point to emphasize will be the increase in demand for and regional disparities in in-home care. From 2020 to 2040, in-home healthcare demand is projected to increase by 43% for people age 75 and older and by 62% for people age 85 and older, and meeting this demand will require rapid efforts to establish in-home care provision systems. While efforts from clinics to establish systems to provide in-home care have made progress in recent years, efforts from hospitals to develop systems to provide visiting in-home care are still behind.

Examining projections by region, by 2040, in-home care demand is expected to increase by 50% or more in 66 secondary care areas and to decrease in 23 care areas, mainly those with small populations. As this projection shows, there will be significant regional differences in in-home care demand, so developing systems that reflect local circumstances will be vital.

Reporting care bed and hospital functions

Care beds were initially arranged into four categories: the advanced acute phase, the acute phase, the convalescent phase, and the chronic phase. In FY2024, a new category of wards called “integrated community care wards” was added to the medical service fee schedule. As part of the integrated community care system, their intended use is to provide support to patients in stable condition after acute phase treatment so they can recuperate in familiar community settings. Later, in FY2024, another new category of wards called “integrated community medical wards” was added in response to an increase in emergency transports for senior citizens, particularly among people with mild or moderate conditions. These wards provide integrated support to senior citizens for speedy rehabilitation and return to the home.

However, the existing categorization of care beds was determined with disease courses for younger generations in mind, so it has been criticized as inadequate for responding to the admission and discharge patterns of senior citizens age 85 and older, or to their diverse medical needs.

In response to these and similar issues, and to accommodate the increasing number of emergency transports for senior citizens by 2040, it has been proposed that beds categorized as “convalescent care beds” be recategorized as “integrated care beds” whose function will combine a portion of acute care beds and convalescent care beds. Discussions at the Government’s study group are also examining the possibility of adding “Health Facility Classification Reports” describing the functions of each health facility alongside Hospital Bed Classification Reports in New Regional Medical Care Visions. Specifically, when arranging health facilities by function, they may be categorized by capacity for providing emergency care to senior citizens, collaboration with in-home care, capacity to serve as centers for acute care, or capacity to provide specialist health services. The aim of introducing “Health Facility Classification Reports” is to help clarify the division of roles among health facilities in each community as well as to promote collaboration, reorganization, and consolidation among health institutions.

■Addressing the uneven distribution of physicians

Background

As of FY2024, projections show that supply and demand for physicians is likely to balance out throughout Japan by 2029, but the uneven distribution of physicians among regions has been highlighted as an issue. As for the number of clinics, it is decreasing in secondary care areas with small populations and increasing in large care areas, so there is a widening gap among care areas. In addition to aging among physicians who operate clinics, those who try to open new clinics in areas with small populations are likely to encounter difficulties, so there are concerns about physician shortages becoming even more severe in such areas in the future.

Current measures to address the uneven distribution of physicians and their impact

Current efforts to address the uneven distribution of physicians generally fall under three pillars: initiatives in the physician training process; initiatives addressing individual prefectures; and work style reform for physicians. Specifically, initiatives in the physician training process aim to address uneven regional distribution by establishing regional quotas (which are quotas for the number of physicians who can practice in certain regions or departments) at university medical schools and clinical trainee quotas for each prefecture. These quotas will be determined while keeping in mind regions with few physicians. As a result of these efforts, as of 2024, approx. 9,400 physicians had been trained under the regional quota system. In addition, each prefecture has also been obligated to grasp circumstances surrounding the uneven distribution of physicians, to formulate plans for securing physicians, and to implement concrete measures based on those plans. Despite these efforts, this issue has yet to be resolved.

The Comprehensive Package for Correcting the Uneven Distribution of Physicians

To correct the uneven regional distribution of physicians, on December 25, 2024, the MHLW formulated the “Comprehensive Package of Measures for Correcting the Uneven Distribution of Physicians.” It has three basic concepts. The first concept is based on the recognition that it will not be possible to correct the uneven distribution of physicians with only a single initiative, and states, “While advancing initiatives based on plans to secure physicians, comprehensive measures will be implemented and include a combination of economic incentives, mutual support systems for health institutions in communities, and efforts taken through the physician training process.” The second is, “Taking into account aspects like physicians’ values and career paths, working and living environments, and flexible working practices, physicians of all generations including mid-career and senior physicians will be approached.” The third and final concept is, “Clearly identify which areas require support not only by considering indicators for the uneven distribution of physicians, but also by considering regional characteristics such as number of physicians per inhabitable land area or access, and implement measures that surpass conventional efforts to address the needs of remote areas.”

Under these basic concepts, the Government identified five specific initiatives to include in its Comprehensive Package for Correcting the Uneven Distribution Of Physicians (Table 1). Two areas of initiatives were discussed during this lecture. The first is ensuring that plans to secure physicians are effective. Specifically, the first step will be to identify areas where physicians are unevenly distributed that will require intensive support, and to prioritize them with focused efforts to correct the distribution. The Government is also requiring prefectures to formulate plans for correcting the uneven distribution of physicians in the areas identified. The second step will be to construct frameworks for mutual support among local health institutions. Specifically, the Government plans to expand the number of health institutions subject to the requirement for administrative staff to have experience working in areas with a small number of physicians, or similar regions. The MHLW currently has a system for recognizing physicians who have served in areas with few physicians for a certain period (six months or more) and who performed the necessary duties to provide healthcare in those areas during that period. Possessing such experience is now a requirement for administrative staff at certain health institutions. As part of the comprehensive package, in the future, health institutions that must require administrative staff to possess that experience will be expanded, and the minimum service period will be extended from six months to one year. There are also plans in place to provide physicians who want to establish new practices in areas with many outpatient physicians with requests to provide the healthcare functions needed in those areas. Specifically, in areas with many outpatient physicians, prefectures will be able to ask physicians who wish to establish new practices to submit notifications with information like the healthcare functions they plan to provide six months before opening and to participate in discussions on local outpatient care. Prefectures will also be able to request these physicians to provide the care that the region lacks.

In this manner, efforts are being made through the Comprehensive Package of Measures for Correcting the Uneven Distribution of Physicians to respond to rapid demographic changes in each region and to ensure the necessary future healthcare provision systems are in place.

(Table 1) Specific measures in the Comprehensive Package of Measures for Correcting the Uneven Distribution of Physicians

| Area of initiative | Specific content of initiative |

| 1. Ensure plans to secure physicians are effective | (1) Identify areas that require intensive support to address uneven distribution |

| (2) Formulate plans to correct the uneven distribution of physicians | |

| 2. Frameworks for mutual support among local health institutions | (1) Expand health institutions where administrative staff must have experience serving areas with few physicians, etc. and similar actions |

| (2) Submit requests to those who wish to establish new health institutions in areas with many outpatient physicians to provide healthcare functions needed in the region | |

| (3) Establish requirements for administrative staff at insured healthcare institutions | |

| 3. Economic incentives and other measures to address the uneven regional distribution of physicians | (1) Provide economic incentives |

| (2) Support the nationwide matching function | |

| (3) Support recurrent education | |

| (4) Form partnership agreements between prefectures and university hospitals and other facilities | |

| 4. Efforts taken through the physician training process | (1) Establish quotas for medical schools and regions |

| (2) Provide clinical training | |

| 5. Efforts to correct the uneven distribution of physicians among medical departments |

A lively discussion with the audience was held during the Q&A session after the lecture. Topics discussed included the possibility of reviewing secondary care areas, proposals on specific measures to address the uneven distribution of physicians (increasing regional quotas, establishing training systems for young physicians in rural areas, etc.), and implementing work style reform to enhance activities for physicians of all genders.

(Photo : Kazunori Izawa)

■Profile:

Dr. Keiko Morimitsu (Director General, Medical Affairs Bureau, Health, Labour and Welfare)

After graduating from Saga Medical University in 1992, she joined the Ministry of Health and Welfare. She served in various positions, including secondment to the Health Services Division of the Planning and Coordination Bureau of the Environment Agency, the School Health Education Division of the Physical Education Bureau of the Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture, and the Health Promotion Support Division of the Health and Medical Care Department of Saitama Prefecture, before being appointed assistant director of the Medical Care Division of the Health Insurance Bureau of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), and director of the Research and Development Division of the Health Policy Bureau. She was appointed the first female director of the Health Care Division of the Health Insurance Bureau in 2018. In 2022, she was promoted to deputy director general for Health Care and Long term Care Integration and Data Health Reform of the Minister’s Secretariat, MHLW (concurrently serving in the Medical Policy Bureau and the Elderly Health Bureau); then director general for Crisis Management and Medical Technology, Minister’s Secretariat, MHLW in 2023 (concurrently serving in the Insurance Bureau); and in 2024, became the first female director general of the Ministry’s Health Policy Bureau.

On November 26, 2024, Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) hosted the 56th Special Breakfast Meeting, titled “From Insights to Impact: How Do We Ensure Health Policy and Systems Research and Learning Accelerates Achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)?” The event was held shortly after the launch of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research’s 2024-28 strategy, “Aiming for Impact.”

We were honored to welcome the Honorable Helen Clark, Chair of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research Board, former Prime Minister of New Zealand, and former Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), as our keynote speaker. The keynote was followed by a panel discussion featuring global experts, including Anders Nordström (Former Swedish Ambassador for Global Health), Dr. Naoko Yamamoto (Professor, International University of Health and Welfare / Director, Global Medical Cooperation Center), and Mr. Ryoji Noritake (Chair, HGPI), moderated by Dr. Kumanan Rasanathan (Executive Director, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, WHO).

The meeting provided a unique platform for high-level dialogue on how health policy and systems research (HPSR) can effectively contribute to SDG achievement, and how to overcome the barriers that prevent research from being translated into actionable policies and improved health outcomes.

■Key Takeaways:

- Evidence-based research is fundamental to strengthening health systems globally. It is a strategic investment that can address current global health challenges and contribute to building stronger, more efficient, and more equitable systems.

- The focus should not only be on the “what” but also on the “how.” A clear understanding and articulation of both are essential for impactful policy formulation and implementation.

- A strong commitment is required to leverage health policy and systems research to improve health outcomes by fostering interdisciplinary and cross-sectoral collaboration.

- The panel highlighted the need to bridge gaps between researchers and policymakers by establishing common language and shared objectives, while acknowledging differences in time horizons and incentive structures.

- Discussions emphasized the importance of fostering mutual understanding, especially between those who generate evidence and those who shape policies.

- Promoting continuous dialogue and knowledge-sharing among diverse experts, practitioners, and communities is crucial. It is equally important to listen to and amplify the voices of under-represented regions and groups.

- The role of international organizations was also discussed, with calls for them to play a more active role in supporting HPSR, strengthening country-level capacities, and promoting equity in global health research and policy.

■ Keynote Speech

In her keynote address, the Honorable Helen Clark called on health systems and researchers to “do business unusually” by stepping away from outdated practices that fail to deliver meaningful results. She stressed that the COVID-19 pandemic exposed both the strengths and weaknesses of health systems globally and highlighted the urgent need to apply these lessons to build more resilient and responsive systems capable of withstanding future crises.

Ms. Clark emphasized that collaboration between researchers and policymakers is critical to translating evidence into impact. Without strong political will and alignment, even the most robust research risks being left unused. She cited Japan as a positive example where collaboration between researchers and policymakers has been institutionalized, providing a valuable model for other nations.

She further highlighted that research is not a luxury, but a strategic investment essential for creating more effective, equitable, and sustainable health systems worldwide. Concluding her remarks, Ms. Clark expressed her vision of a future where health policy and systems research drives real solutions to global challenges through broad, interdisciplinary cooperation.

■ Main Themes from the Panel Discussion

Barriers Faced by Health Systems

There are different barriers but one of the main barriers is bringing different people from different backgrounds and fields to leverage solutions. It is not always simple to bring people together, however, it is necessary in this context to generate global solutions. Moreover, the fact is that up until now, health systems have been focusing on the ‘whats’ and not on the ‘hows’, this is another barrier. This is mainly because we believe in evidence and research and this is how we function as researchers; however, when it comes to policy making, we need to know the ‘hows’ and to focus on the ‘hows’. The reality is that politicians do not believe in research and we that work in health systems lack understanding on the ‘whats’ and the ‘hows’. We must develop our understanding of decision-making on both a private and a public level because policy learns from evidence, but it is essential to comprehend the evidence and how best to use it to bring solutions.

Additional barriers for health system research are language, concept, and definition. Research uses academic language and concepts that are ambiguous to the layman; a common language and a common understanding is necessary for health system research to be successful and effective. Research is mainly conducted for non-researchers and the outcome of research is also aimed at non-researchers; therefore, it is crucial that researchers learn to communicate simply without academic jargon that is cryptic to the non-researchers.

Timeframe is another barrier as policy makers need to have a long-term vision to plan policies ahead of time, they also need to consider time and how best to use their time. This is different for researchers as their concept of time and the way that they use time is specific to the research context. Therefore, researchers need to learn to understand their timeframe in the political context. Additionally, there is also a lack of collaboration between different groups of experts in health systems, and this is required to have effective outcome measures and to be able to share those outcome measures.

The main barrier for health system research in Japan is that the concept of evidence needs to be clearly defined and more polished. Seeing as humans are more emotional than rational, there is a need for more granularity in research because politicians operate rationally. As a result, there is a disparity; however, the cause of the granularity differs. Therefore, there is a need for ethnographic research in health system research to understand why this granularity occurs. Mr. Noritake gave the example of the Cancer Act in Japan to explain his point on granularity. When the Cancer Basic Act went into effect, the government set the goal for 47 prefectures to have regional cancer control act. However, the reality to this approach is that each prefecture is different and will implement the act differently and therefore will obtain different results. Thus, it is necessary for the government to make a concrete plan that each local government can appropriate. By doing this, prefectures can learn from each other, and prefectures that are similar in size or that have the same context may be able to collaborate and measure the outcomes together.

Essential Ingredients for Impactful Health Systems Research

The research question and the methodology must be correct, and different disciplines need to be incorporated from the beginning. It is imperative to understand the research question to establish the right methodology. Practitioners need to be incorporated from the very beginning once the research question has been adequately defined. Research will become more relevant and effective once those implementing and practicing the results of research outcomes are involved from the onset because they can provide their perspective and share their experiences, which will enrich the research and especially the methodological approach employed. Moreover, people’s values are important, and researchers must comprehend this and conduct research that delves into people’s behaviour in order to properly understand what causes people to change their behaviour. If people’s values and experiences are at the forefront of research, it becomes easier to conduct research that speaks to these values.

Timeliness is a key factor for health systems to have a meaningful impact on health and development. Making significant impact in policy development needs momentum and time is essential for momentum. Moreover, health policy and system researchers need to be visionary and dialogue with diverse communities; by doing this, they will be able to employ the data obtained from these communities to depict the reality as accurately as possible. Collaborating with diverse communities not only enriches research but it also makes a difference in the communities because they see how essential their voice is to research. Policy development and implementation must be evidence-based, using evidence sourced from the existing reality in a balanced way. Comprehending the existing reality will facilitate the identification of the steps necessary to effectively ameliorate the current reality.

Additionally, the ‘hows’ needs to be persuasive for health policy and system research to be impactful because without the ‘hows’, we cannot achieve the ‘whats’; without the ‘hows’, the evidence would be in vain. Moreover, the level of evidence is important; the level of evidence is important because there is a need to understand that the decision-making process depends on the power of politics and the power dynamics in politics. For example, when building bridges, the resources and the raw materials required to build bridges are like the evidence that we provide. However, where to build the bridge is political and it is the decision makers that make this decision not the researchers. Therefore, it is essential that researchers comprehend the power dynamics in decision-making relating to health policy and provide evidence that can influence the way that the decision is made. The source of this evidence will not be from the researchers alone, but the people for whom research is being conducted, those who benefit from the research outcomes. This is one of the main foci of the HGPI; to promote the voice of the public in policy-making.

The Role of Global Institutions

Research must be in the DNA of international organisations. Moreover, it is important to focus on the ‘hows’, not just the ‘whats’ and to understand how the ‘hows’ work and whether they work or not by examining the outcomes of health policies. Foresight is also imperative in health system research; research often tends to look back; however international organisations need to stimulate foresight in research to be able to predict and prepare for unexpected circumstances and potential scenarios. In addition, organisations like the WHO need to return and focus on their core mandate and work closer with countries on advancing health system research.

Furthermore, international organisations need to encourage and focus on voices from under-represented regions and established a balanced representation as voices from Western countries are often too loud, leaving voices from Asian or African countries are neglected resulting in an imbalance and polarisation. It is also essential that international organisations like the UN to continue to advocate human rights that promote safe, free, and ethical research; the reality is that research often reveals unethical facts that need to be addressed, and adequate support must be provided to researchers to promote fair science.

Additionally, international organisations need to continue to broaden their knowledge scope by collecting best practices from other regions to learn from them. For example, in the cardiovascular disease (CVD) project conducted by the HGPI, the HGPI collaborated with Thailand and this collaboration was enrichening for the HGPI as they learned how to promote policies regarding CVD even with limited resources from Thailand. Moreover, organisations like the UN need to encourage granularity across regions, countries, and diseases. Cross-disease granularity is especially primordial as lessons learned from policies made for one disease can be useful for another disease. For example, the discussions that are currently occurring in Japan regarding dementia and how people with dementia can still contribute to society, are the same discussions that took place 20 years ago. Therefore, there is a cross-disease discussion with dementia and cancer currently occurring in Japan, which is enrichening as different dementia patients can learn from cancer patients and vice versa.

It is also essential for international organisations need to think about the specific stories that move people, understand these stories and evoke the right change using people’s stories, not just their own agendas. There must be an alignment to budget cycles in international organisations, as well as an understanding of the values that drive policies. Without understanding the values and the driving forces behind health policies, it would be tasking to evoke change. International organisations need to continue to promote quality health systems research and bring countries together to learn from each other in a balanced manner, in which every country’s voice is heard and valued. It is imperative that organisations like the UN remain humble about their work and continue to promote this type of attitude in health systems research.

Making a Difference with Health Systems Research

The process of the research needs to be used to encourage people to live well not only to focus on the outcomes; health system research should be about encouraging people to live well by first helping people to understand why it is important to live well and by reaching an agreement. Research also needs to focus on helping society develop the understanding that the most important outcome measures is the number of healthy years we live, not necessarily the number of years; it is more important to add health to life not necessarily years to life. It is necessary that the focus must change to adding health to life because adding years to life without health is futile.

For health systems to be effective, and for health system research to be impactful, we must not ignore what motivates and what drives people intrinsically; it is the intrinsic drive that will result in long-lasting behavioural change. For example, the contribution of art to health is important and it is a fact that cannot be neglected by science. Art has a significant impact on mental well-being and this is often overlooked by science. It is necessary that scientists comprehend the importance of factors like art and the impact that it has on health and focus on promoting these factors with health to encourage durable health behaviour changes.

In addition, to make a difference with health system research, we need to embrace the fact that we fail and that we need to take risks; a reform can only occur when we take risks, and we learn from these risks. Furthermore, it is imperative to promote knowledge development and continuous dialogue with different people with different expertise from different backgrounds, and to value and listen to the voices of these individuals with precision and accuracy.

To make a difference with health systems research, there must be a balanced focus on both outcomes and health equities, and a contribution to building trust so that research becomes a part of societal dialogue. Moreover, a paradigm shift from involvement to co-creation is essential, in which ongoing collaboration with health services users and the public is continuously encouraged and promoted.

We need to understand that health systems differ from one country to another, and countries can learn from each other; however, there needs to be balanced alignment in our healthcare systems to bring global solutions to the global challenges that we are facing. The global challenges that we are experiencing in the world today are significant challenges; however, we have the tools through research to generate solutions and to play a part in addressing these challenges.

■Q&A

A dynamic and lively discussion took place during the Q&A session. Topics include the role of each individual in appropriating the SDGs for themselves to achieve the SDG goals, the contribution of art to science and health, and learning how to fail well in research. Building trust in pharmaceutical companies, developing research literacy and learning how to adequately assess health systems were also discussed during this session.

(Photographed by: Kazunori Izawa)

■Profile:

Helen Clark (Chair of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research Board/ Former Prime Minister of New Zealand/ Former Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP))

Helen Clark was Prime Minister of New Zealand from 1999–2008 and a Member of Parliament for 27 years. She advocated strongly for economic and social justice, sustainability and climate action as well as for multilateralism. Helen served two terms as Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and as Chair of the United Nations Development Group from 2009-2017. Earlier, Helen taught in the Political Studies Department of the University of Auckland, from which she had graduated with BA and MA (Hons) degrees. Helen advocates for sustainable development, climate action, gender equality and women’s leadership, peace and justice, and action on pressing global health issues. In July 2020, she was appointed by the Director-General of the World Health Organisation as Co-Chair of the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response. Amongst others, she chairs the boards of the Extractive Industries Transparency Organisation, the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health.

Anders Nordström (Member of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research Board/ Former Ambassador for Global Health, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sweden)

Anders Nordström is the former Swedish Ambassador for Global Health. He is a medical doctor. Today he is associated with the Karolinska Institute and the Stockholm School of Economics. He is currently a member of the Alliance for Health Systems Research’s board, the SUN-Lancet PRIME Commission, the International Vaccine Institute Global Advisory Group of Experts, and the Virchow Foundation for Global Health Council. Recently he headed the Secretariat for the Independent Panel for Pandemic Preparedness and Response (2020-21). He served as Acting Director-General for WHO (May 2006 – January 2007) and as Assistant Director General for General Management (2003-2006), Assistant Director General for Health Systems and Services (2007) and Head of the WHO Country Office in Sierra Leone (2015-17). As the Interim Executive Director, he established the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria as a legal entity in 2002. He has previously served as board member of the Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, GAVI, UNAIDS and PMNCH and chaired a number of international working groups and processes. He was the Director-General for the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (2007-2010).

Kumanan Rasanathan (Executive Director, Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research, World Health Organization (WHO))

Dr Rasanathan is the Executive Director of the Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland. He is a public health physician with a strong background in health policy and systems research and extensive experience working at different levels of the World Health Organization and within the wider UN system. During his almost 25 years working in health systems, career highlights have included serving as Incident Manager for WHO for the COVID-19 response in Cambodia, helping to drive the development of the Sustainable Development Goal health agenda while at UNICEF, contributing to the work of the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, co-writing the 2008 WHO World Health Report on primary health care, and running meningococcal vaccine trials that enabled vaccine licensure and roll-out in New Zealand. Dr Rasanathan served as an elected board member of Health Systems Global from 2016-2020, was a Rockefeller Foundation Global Fellow in Social Innovation from 2013-2014 and was a member of the Forum on Microbial Threats of the US National Academy of Medicine from 2017-2023.

Naoko Yamamoto (Professor, International University of Health and Welfare / Director, Global Medical Cooperation Center)

Dr. Naoko Yamamoto brings nearly 30 years of experience working on health-related issues. She served as Senior Assistant Minister for Global Health in Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MoHLW). In this capacity, she was heavily involved in Japan’s global health leadership hosting and organizing the International Conference on Universal Health Coverage (UHC) in 2015, and supporting the compilation of the G7 Ise-Shima Vision for Global Health and Kobe Communique of the G7 Health Ministers’ Meeting in 2016. Both of which highlighted the importance of promoting UHC. Prior to this role, she served in numerous health-related positions within the government of Japan, including as Director General of the Hokkaido Regional Bureau of Health and Welfare, Director of Diseases Control Division at MoHLW, Director of the Health and Medical Division at the Ministry of Defense, and Counsellor to the Permanent Mission of Japan to the United Nations. From 2017 to 2022, she served as the Assistant Director-General of Division of UHC/Health Systems (in 2017) and Division of UHC/Healthier Populations (2018-2022) in the World Health Organization (WHO). She retired from the WHO at the end of November 2022 and has held her current position since December 2022. She holds a medical degree, a Ph.D. in epidemiology, and a Master’s degree in Public Health.

|

Kazumasa Nagayama

|

|

Moderna extends its heartfelt congratulations to Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) on its 20th anniversary. Since our founding in 2010, Moderna has been committed to improving people’s health by advancing vaccines and therapeutics rooted in messenger RNA (mRNA) technology. In 2021, we established Moderna Japan, driven by our mission to “deliver the greatest possible impact to people through mRNA medicines.” Through our COVID-19 vaccine, we have strived to contribute to the health of people in Japan. mRNA technology holds the potential to revolutionize how humanity combats disease. At Moderna, we are actively conducting research and development across various fields, including infectious diseases, rare diseases, cardiovascular conditions, autoimmune disorders, and cancer treatment. We believe that this technology can offer new solutions for medical challenges that have historically been difficult to address. Inspired by HGPI’s expertise and proactive approach, we are honored to continue tackling global challenges together. Congratulations once again on HGPI’s 20th anniversary. We sincerely wish you continued success and further accomplishments in the years to come. |

|

■Company information |

|

Okuda Osamu |

|

We sincerely congratulate Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) on its 20th anniversary. Since its founding in 1925, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. has been committed to contributing to global healthcare and human health through the research and development of innovative pharmaceuticals. After initiating a strategic alliance with the Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche in 2002, we have aimed to become a top innovator in the healthcare industry, realizing advanced and sustainable patient-centric healthcare. Under the three core values of “patient centric”, “pioneering spirit,” and “integrity,” we have been dedicated to creating innovative new drugs. From its inception, we have supported HGPI’s noble philosophy and have been a supporting member since 2012. We have also participated in and cooperated with important projects such as “The Project for Considering the Future of Precision Medicine with Industry, Government, Academia, and Civil Society” and “Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) Support Project”. In addition, we are grateful for the valuable opportunities provided by your organization, including dispatching our employees to the Health Policy Academy. HGPI’s highly specialized policy recommendations have significantly contributed to improving Japan’s healthcare standards and solving challenges. Our company looks forward to HGPI’s continued activities toward the development of healthcare policies and the resolution of social issues in Japan. On this 20th anniversary milestone, we sincerely wish for HGPI’s further growth and success. |

|

■Company information |

|

Masashi Miyamoto |

|

We would like to sincerely congratulate Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) on its remarkable 20th anniversary. In the field of health and medicine where HGPI operates, under our management philosophy of “the Kyowa Kirin Group companies strive to contribute to the health and well-being of people around the world by creating new value through the pursuit of advances in life sciences and technologies,” and as a Japan-based Global Specialty Pharmaceutical Company, we are striving to utilize diverse drug discovery technologies, such as our unique antibody technologies, to discover innovative new drugs that will make patients and their caregivers smile. We have designated as our vision for 2030, “Kyowa Kirin will realize the successful creation and delivery of life-changing value that ultimately makes people smile, as a Japan-based Global Specialty Pharmaceutical Company built on the diverse team of experts with shared passion for innovation.” By identifying unmet medical needs and creating new pharmaceuticals and solutions to meet those needs, and by innovating across the company, it is Kyowa Kirin’s aim to create life-changing value that brings smiles to people suffering from disease and gives them hope that their lives can change dramatically for the better. We deeply respect the passionate activities in the health and medical fields that HGPI has woven since its establishment, and the numerous achievements that have emerged both domestically and internationally from these efforts. We also wish for the continued growth and success of your organization in realizing a healthier and more prosperous society for people. Congratulations on your 20th anniversary. |

|

■Company information |

*A video message by Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has been released on the Prime Minister’s Office of Japan website.(Japanese only with English subtitles) (September 26, 2024)

Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) and AMR Alliance Japan hosted a side event on the 25th of September in conjunction with the 79th UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in New York City. The event titled, “Global Action on AMR: Advancing Healthy Longevity and Sustainability under UHC” brought together a panel of experts from government, industry, academia, and civil society including AMR survivors.

The discussions centered on AMR contributions from Japan and expectations towards future international collaboration for better AMR policy around the world. The event was followed by a networking reception where participants and panelists engaged in a lively exchange of ideas and views on AMR, our society, and our future.

In commemoration of this side event, Prime Minister of Japan, Fumio Kishida sent a pre-recorded video message and Dame Sally Davies UK Government Special Envoy on Antimicrobial Resistance sent a pre-written message.

The second UN General Assembly High-Level Meeting on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) was held on 26 September, for the first time in eight years since 2016. AMR was placed again on the agenda where this time a political declaration was adopted to accelerate implementation to tackle the challenges posed by AMR.

.

*A summary of the discussion points from this side event will be published in due course.

[Overview]

- Date & Time: September 25, 2024; 14:00-16:00 (EDT)

- Venue: The Nippon Club (145 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019)

- Language: English

- Host: Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI), AMR Alliance Japan

- Co-host: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan

- In partnership with: AMR Multi-Stakeholder Partnership Platform, CARB-X, GARDP, International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA), Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE) and Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA)

- Supported by: Nikkei FT Communicable Disease Conference

[Program] (titles omitted; in alphabetical order, EDT)

| 14:00-14:05 | Welcoming Remarks *pre-recorded video |

|

Fumio Kishida (Prime Minister of Japan) |

|

| 14:05-14:15 | Opening Remarks |

|

Yasuhisa Shiozaki (Chairman, Keisou Nippon Initiative Foundation / Member, Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance / Chair, Executive Committee on Global Health and Human Security, Japan Center for International Exchange (JCIE)) |

|

| 14:15-14:20 | Introductory Explanation |

Yui Kohno (Manager, Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) / AMR Alliance Japan) |

|

| 14:20-15:20 | Roundtable Discussion “Contributions from Japan and Expectations towards Japan for Better AMR Policy in the World” |

|

Speakers: |

|

|

Peter Beyer (Deputy Executive Director, GARDP) |

|

|

Vanessa Carter (Chair, WHO Task Force of AMR Survivors / Executive Director, The AMR Narrative) |

|

|

Christos Christou (International President, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)) |

|

|

Hajime Inoue (Assistant Minister for Global Health and Welfare, Minister’s Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Government of Japan) |

|

|

Norio Ohmagari (Director, AMR Clinical Reference Center, National Center for Global Health and Medicine (NCGM)) |

|

|

Kevin Outterson (Professor, Boston University / Executive Director, CARB-X) |

|

|

Takuko Sawada (Japan Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association (JPMA) / Director and Vice Chairperson of the Board, Shionogi & Co., Ltd.) |

|

|

Thanawat Tiensin (AMR Multistakeholder Platform / Assistant Director-General and Chief Veterinarian, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) / Director, Animal Production and Health Division (NSA), FAO)) |

|

|

Anna Wechsberg (International Director, Department of Health and Social Care, UK) |

|

|

Moderator: |

|

| 15:20-15:30 | Closing Remarks |

| 15:30-16:00 | Networking Reception |

(Photographed by: Christopher Cataldi)

Message from Dame Sally Davies

AMR impacts all of us. Over 1.1million people died from AMR in 2021, and by 2050, more than 39million people will die. They could be any one of us, from anywhere in the world, although the burden falls the greatest in western sub-Saharan Africa, Tropical Latin America, high-income North America, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. That’s why this High-Level Meeting is key to driving global action and I am grateful to HGPI and the AMR Alliance Japan for corralling ambition and action, and for the crucial demonstration of support from Fumio Kishida, Prime Minister of Japan. The High-Level Meeting will put access at the heart of our action:

- Access to antibiotics, which could save 92 million lives between 2025 and 2050.

- Access to sustainable financing – we need to leverage and make accessible the financing that is already out there in multilateral streams and development banks to fund National Action Plans on AMR.

- Access to education, scaling up some of the fantastic initiatives across the world, such as AMR art and drama clubs for schools in Tanzania.

The first key step will be Member States agreeing to establish a new independent science panel on AMR, which we desperately need to assess the evidence that is out there and inform future targets and interventions. I hope the panel will be based at the UN Environment Programme HQ in Nairobi – so it can look at human, animal and environmental aspects of AMR, and be rooted where the burden of AMR is greatest. I look forward to working with you all to deliver on our commitments and making progress to stop 39 million people dying by 2050. Everyone can play a personal and professional role in how they use antibiotics, consume meat, and raise awareness. We can do it, together.

Dame Sally Davies

Special Envoy on Antimicrobial Resistance for the United Kingdom

For the 54th Special Breakfast Meeting, we hosted Mr. Keizo Takemi (Minister of Health Labour and Welfare Member, House of Councillors, Japan).

Mr. Takemi, who has served as Minister of Health, Labour and Welfare since September 2023, delivered a lecture on the future of health and welfare administration.

<Key points of the lecture>

- Japan’s current demographic challenges rooted in a declining birthrate, population aging, and population decline have placed the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) at a historic turning point.

- We must build broad-reaching systems for social and economic vitality throughout Japan and overseas, and create a futuristic and active digital health society.

- To build the aforementioned systems and futuristic society, it will be important to promote innovation and digital transformation (DX) in healthcare and engage in global collaboration through the Japan Institute for Health Security (JIHS) and the UHC Knowledge Hub.

■The future of the domestic health sector

In 2030, Japan’s working population will begin to decline rapidly, and the number of senior citizens will peak in 2040. This will be followed by a decline in the elderly population and a rapid decline in the total population. Our major theme is determining how to rebuild society and the economy so Japan can maintain its position in the leading group in the international community.

It is clear that the top priority in health system reform will be to promote digital transformation (DX) in healthcare and long-term care. It will also be necessary to rebuild the social security system for all generations so it is sustainable and has the capacity to absorb innovation. Innovation in medicine and healthcare is extremely expensive, and it is difficult to cover everything with the health system’s existing framework for medical financial resources. We must adopt an attitude that emphasizes securing new financial resources for healthcare and incorporating scientific advances into health insurance. Healthcare and long-term care must be repositioned as the subjects of industrial policy, and the MHLW must develop policies that draw out potential.

We must also think of each item in this set of policy transitions in an international context. If industrial policy is not expanded with international collaboration in human resources, capital, and technology, it could result in an extremely narrow-minded form of nationalism, in which we try to resolve every issue with domestic companies alone. With this vision, we will create a futuristic and active digital health society by expanding innovation through industrial policy in healthcare and long-term care and international collaboration for steady progress in revitalizing Japan’s society and economy.

■Toward achieving a futuristic and active digital health society

In 2050, Asia will be home to almost 70% of the global population age 65 or older. Many Asian countries will not be able to keep up with the changes in national disease profiles that occur as populations age, which will cause inappropriate health disparities to grow. Japan is the leading country for population aging in Asia, and is accumulating knowledge in the public sector, the private sector, and in academia. We must process and utilize that knowledge in a strategic and appropriate manner to contribute to reducing health disparities in Asian countries through mutual collaboration that involves the Government using tools like Official Development Assistance (ODA), while the private sector utilizes market mechanisms.

It will also be necessary to establish extremely close links among international and domestic strategies. For example, Japan may be able to promote industrial development in a manner that creates a cycle of labor resources in which long-term care workers are recruited from countries across Asia to fill domestic labor shortages, and those workers then return to leadership positions in their own countries after building work experience in Japan.

Japan must also demonstrate that it is striving to make correct and significant contributions in the international community. For around the past two decades, Japan has been a global leader in universal health coverage (UHC). Strengthening health systems was first introduced as a major policy issue at the G8 Hokkaido Toyako Summit in 2008. Since then, Japan has actively promoted the concept that UHC should be the objective of the health system approach, with the three main elements of human resources, information, and finance. For two years in a row during the Abe administration, under the leadership of Japan, leaders like the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO), the President of the World Bank, and the Executive Director of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) came together to confirm the importance of UHC at international conferences held before the United Nations General Assembly. These efforts have led to the inclusion of UHC in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).